Ever wonder why a slice of American cheesecake feels richer, denser, and somehow more indulgent than the lighter, fluffy versions you might see on a Japanese menu or the crumbly ricotta cakes of Italy? The answer isn’t magic-it’s a mix of history, dairy choices, baking techniques, and regional preferences that have shaped the classic U.S. version into something uniquely its own.

Quick Takeaways

- American cheesecake relies on cream cheese, not ricotta or quark, giving it a thick, creamy texture.

- Traditional recipes bake the filling in a water bath to avoid cracks.

- Regional styles-New York, Chicago, and New England-highlight subtle ingredient tweaks.

- Compared to Japanese and European cheesecakes, the U.S. version is denser and richer.

- Simple tricks-room‑temperature ingredients, gentle mixing, and gradual cooling-prevent common pitfalls.

What Makes American Cheesecake Unique?

American cheesecake is a baked dessert built around a thick, smooth filling made primarily of cream cheese, eggs, sugar, and a buttery crust. The hallmark is its dense, velvety mouthfeel that stays firm at room temperature yet melts on the tongue.

The cornerstone ingredient, cream cheese is a soft, high‑fat dairy product invented in the United States in the 1870s. Its 33 %-35 % fat content creates the luxurious body that distinguishes American cheesecake from the lower‑fat ricotta‑based versions popular in Europe.

Other flavor‑building components-sour cream, heavy cream, and sometimes a splash of vanilla-add tang and richness, while the crust-usually crushed graham crackers mixed with butter-offers a crunchy contrast.

A Brief History: From Ancient Greece to Modern America

Cheesecake itself dates back to ancient Greece, where wheat flour, cheese, and honey were pressed into a simple cake. Romans carried the idea across Europe, adding eggs and sweeteners, but the texture remained relatively light.

When European settlers arrived in North America, they brought along recipes that used locally available curds. The turning point came in 1872, when a dairyman named William Lawrence accidentally invented cream cheese while trying to reproduce French Neufchâtel. This accidental creation became the base for a new style of cheesecake, first popularized in New York City’s Jewish bakeries.

By the 1920s, the New York cheesecake-a denser, cream‑cheese‑centric version-had become a city staple, thanks in part to the famed Junior’s restaurant, which still claims the “best cheesecake in New York.” The trend spread westward, and regional variations sprouted across the country, each tweaking the original formula while staying true to the core cream‑cheese identity.

Core Ingredients and Their Roles

Understanding each component helps explain why American cheesecake stands apart.

- Cream cheese - Provides the high‑fat body; its tangy flavor is the backbone.

- Sour cream - Adds acidity that balances sweetness and contributes to a smoother crumb.

- Heavy cream - Increases richness and creates a softer, more melt‑in‑the‑mouth texture.

- Eggs - Act as a natural binder and give the filling its structure when baked.

- Sugar - Sweetens; too much can cause a dry texture.

- Graham cracker crust - Offers a buttery, slightly sweet base; the crumbs absorb moisture, anchoring the filling.

Optional add‑ins like lemon zest, melted chocolate, or fruit purées introduce flavor twists without altering the fundamental texture.

Texture and Baking Techniques

The American method relies on a gentle, even heat to keep the filling from over‑coagulating. Two main techniques dominate:

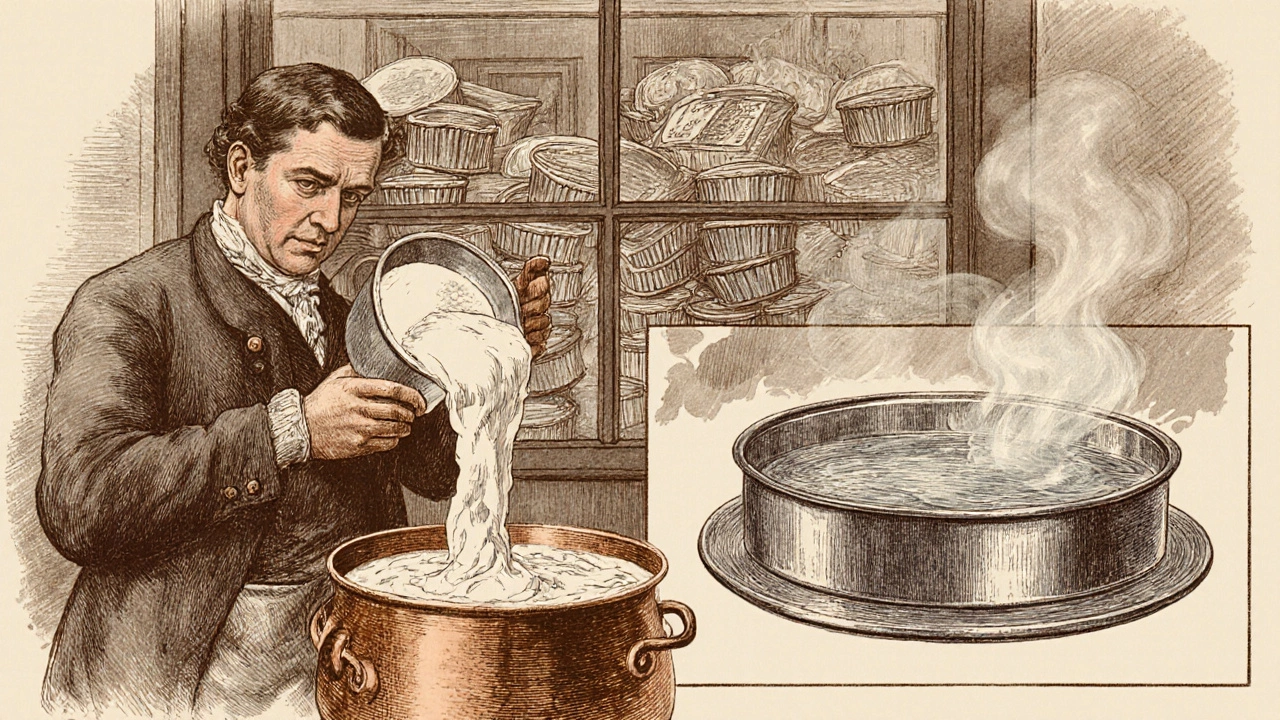

- Water‑bath baking (bain‑marie) - The pan sits in a larger tray filled with hot water. This creates a humid environment that reduces cracking and yields a smooth top.

- Slow cooling - After baking, the cheesecake is left in the turned‑off oven with the door ajar, then chilled in the refrigerator for at least 4 hours. This gradual temperature drop prevents sudden contraction that causes cracks.

Some bakers skip the water bath, opting for a “no‑crack” recipe that reduces the amount of egg or includes a thin layer of sour cream on top. While convenient, the result is often a slightly drier cake.

Regional Styles Within the United States

Even within America, cheesecakes vary by locale.

- New York cheesecake - Ultra‑dense, minimal crust, often topped with a thin sour‑cream glaze.

- Chicago style - Incorporates a deeper graham‑cracker crust, sometimes layered with a fruit compote.

- New England (Boston) cheesecake - Uses a buttery shortbread crust and frequently includes a custard‑like filling with a touch of vanilla bean.

These variations stem from local ingredient availability and cultural preferences, but they all share the cream‑cheese core.

How American Cheesecake Stacks Up Against Global Counterparts

To see the contrast, let’s compare the classic American version with two popular international styles: Japanese soufflé cheesecake and Italian ricotta cheesecake.

| Attribute | American (Cream Cheese) | Japanese (Soufflé) | Italian (Ricotta) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main dairy | Cream cheese (33‑35 % fat) | Cream cheese & whipped egg whites | Ricotta (low‑fat) |

| Texture | Dense, velvety | Light, airy, mousse‑like | Grainy, slightly firm |

| Baking method | Water‑bath, moderate heat | Steam‑baked, low heat | No‑bake or low‑heat bake |

| Typical sweetness | Medium‑high | Low‑medium | Low |

| Common toppings | Sour‑cream glaze, berries | Fresh fruit, powdered sugar | Citrus zest, honey |

The table makes it clear: American cheesecake aims for richness and a buttery mouthfeel, while Japanese cheesecake prizes lightness, and Italian cheesecake showcases the grainy texture of ricotta. If you crave that dense, melt‑in‑your‑mouth feeling, the American style is the go‑to.

Tips for Replicating Authentic American Cheesecake at Home

- Use full‑fat, fresh cream cheese. Let it sit at room temperature for 30 minutes before mixing to avoid lumps.

- Combine the crust ingredients, press firmly into the pan, and bake for 10 minutes at 350 °F (175 °C) to set it before adding the filling.

- Blend the filling on low speed; over‑mixing incorporates too much air, leading to cracks.

- Wrap the springform pan tightly in foil before placing it in the water bath. Prevents water from seeping in.

- After baking, turn the oven off, crack the door open, and let the cheesecake cool inside for 1 hour before refrigerating.

- Apply a thin sour‑cream glaze while the cake is still warm for a glossy finish.

Follow these steps, and you’ll end up with a slice that tastes just like it came from a New York deli.

Common Pitfalls and How to Fix Them

- Cracked top - Often caused by rapid cooling. Use the water‑bath method and cool slowly.

- Grainy texture - Happens when the cream cheese is cold or over‑mixed. Ensure everything is at room temperature and mix just until smooth.

- Dry edges - Can result from over‑baking. The center should still wobble slightly when you shake the pan.

- Soggy crust - Too much moisture from the filling. Press the crust firmly and pre‑bake it.

Adjusting one variable at a time helps you pinpoint the cause and perfect your next bake.

Mini FAQ - All Your Burning Questions Answered

Why does American cheesecake use cream cheese instead of ricotta?

Cream cheese has a higher fat content and a milder tang than ricotta, which creates the dense, creamy texture people associate with the classic U.S. version.

Can I make American cheesecake without a water bath?

You can, but the risk of cracks rises. If you skip the bain‑marie, reduce the egg count slightly and run a low‑heat ‘no‑crack’ recipe that adds a thin layer of sour cream on top.

What’s the ideal serving temperature?

Serve chilled, straight from the fridge. A quick 10‑minute rest at room temperature softens the flavor without sacrificing texture.

How long can leftovers be stored?

Cover tightly and keep refrigerated; it stays fresh for up to 5 days. For longer storage, freeze slices in airtight containers for up to 2 months.

Is there a gluten‑free version?

Yes-swap the graham‑cracker crust for a blend of almond flour, gluten‑free oats, and melted butter. The flavor stays buttery, and the texture remains crisp.

Whether you’re a novice home baker or a seasoned pastry chef, understanding the history, key ingredients, and technique behind the American classic will help you recreate that unmistakable flavor profile. So next time you bite into a creamy slice, you’ll know exactly why it tastes the way it does-and how you can perfect it yourself.